Super smart dude Greg Nuckols made a post over at exodus barbell on the topic of hypertrophy models and effective reps that I thought was worth considering:

https://www.exodus-strength.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=2928&start=40

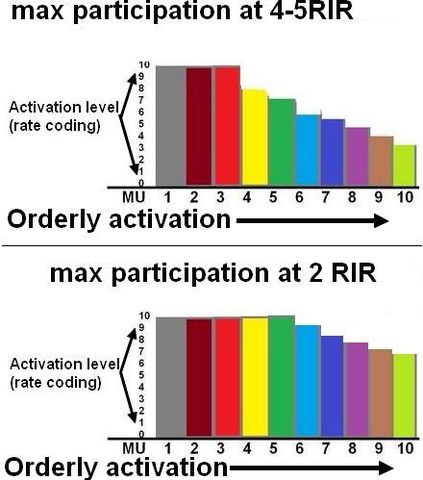

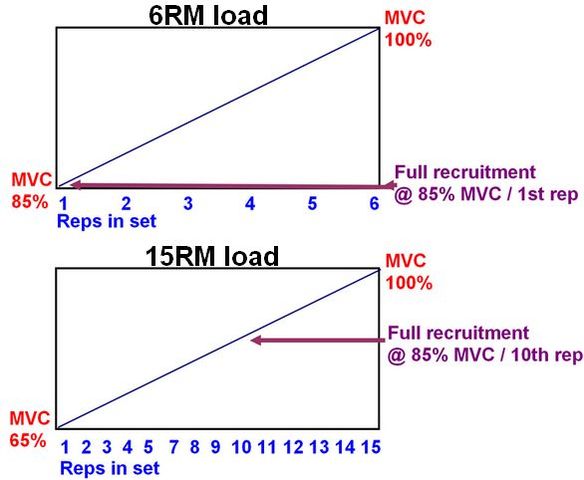

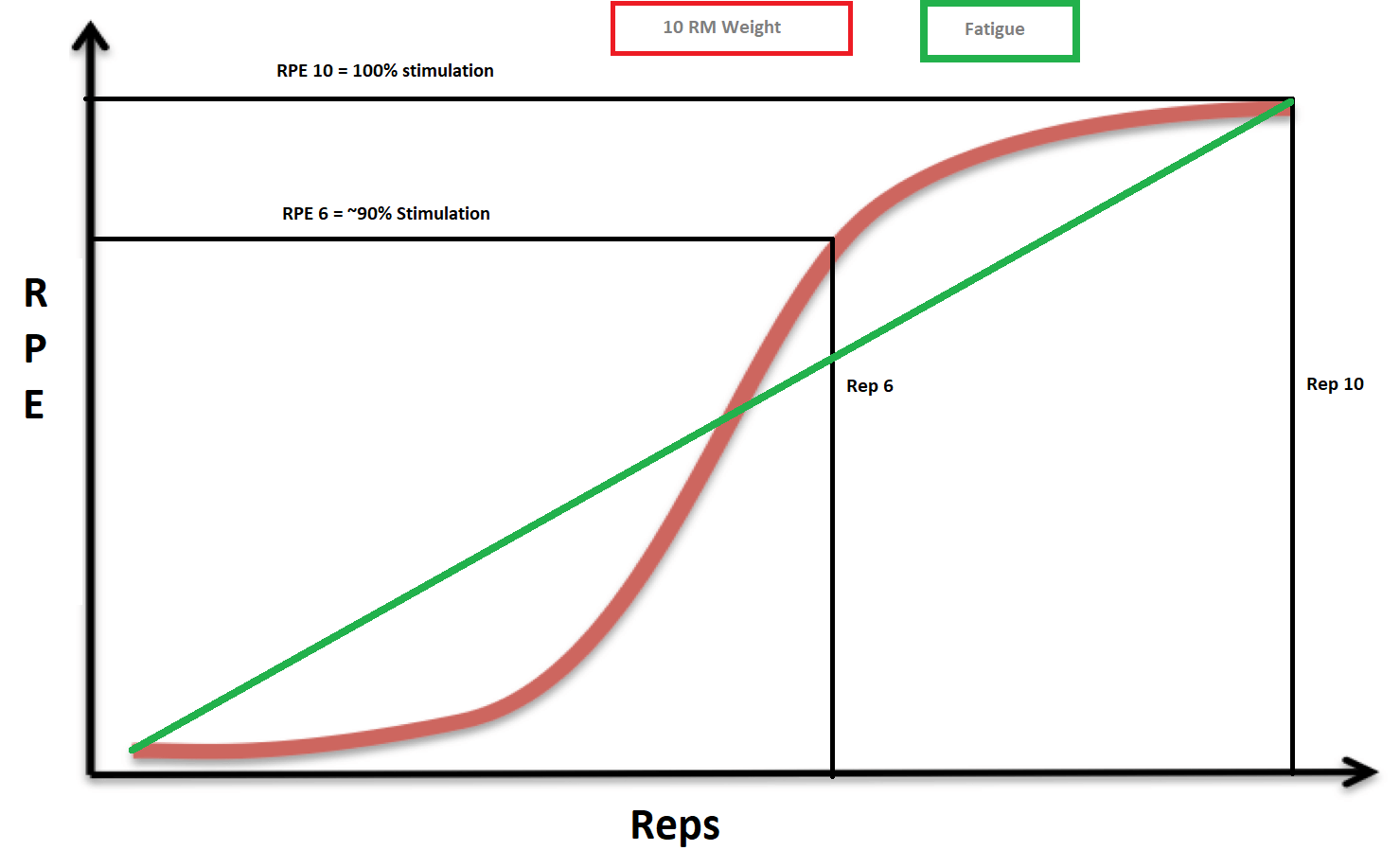

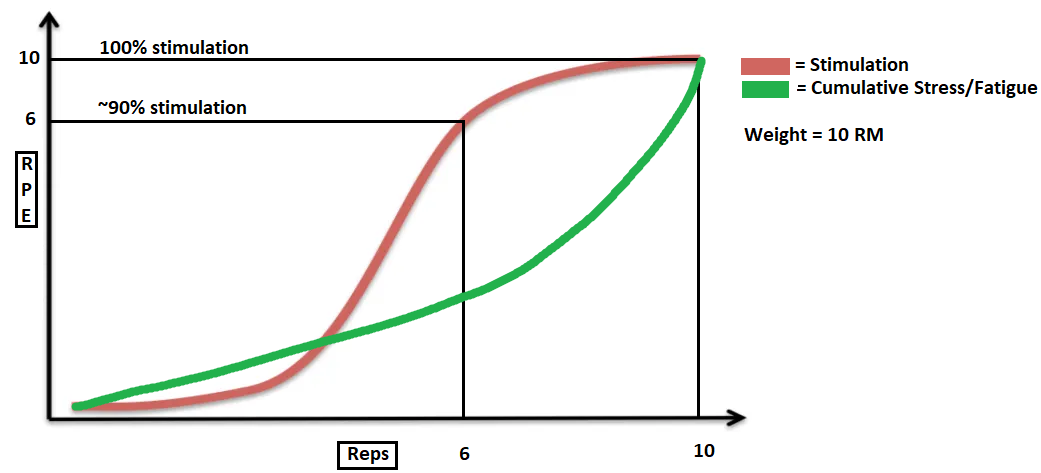

In my previous hypertrophy thread, we discussed the concept of "effective reps" that I first saw introduced by Borge/Blade. Basically the idea that the reps that really "count" in a set seem to be the ones at the end where you are in a state of maximal recruitment, particularly in sets of ~5+. So whether it's a set of 12 or 30, you only get something like 5 "effective" reps per set. Chris Beardlsey talks about the idea at length here:

https://medium.com/@SandCResearch/h...iding-failure-and-using-advanced-90e26d57bca9

What's interesting about Greg's note above is that "effective reps" doesn't seem to be consistent with the fact that training to failure does NOT actually generate more growth per set. One of the consistent findings is that sets that are even near-ish failure, like 2+ reps away, seem to generate just as much hypertrophy, usually. If there are only 5 effective reps per set as per the Beardsley thinking of effective reps, then missing something like half of those should very much NOT result in identical hypertrophy. But it seems to all the same.

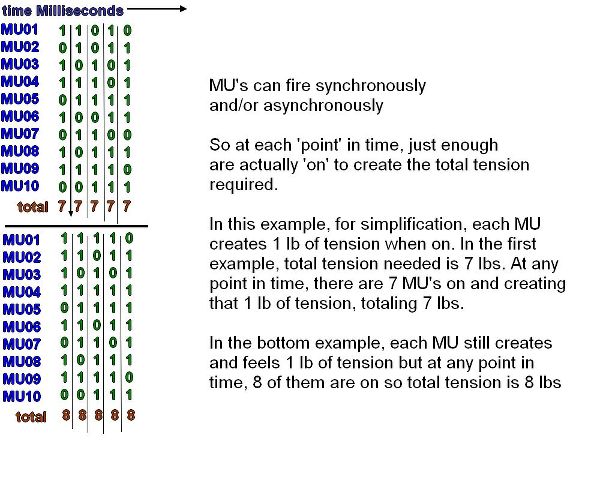

Ron and I were previously speculating that sufficient work at high levels of recruitment and rate coding are necessary to grow optimally, but I'm not sure how to reconcile the rate coding model with this data either. Meaning that not all the motor units' rate coding are maxed out in submaximal sets that are in at least the ballpark of failure (probably still full recruitment), but still they seem to generate as much hypertrophy.

I was reminded of the old idea of growth being turned "on" ala HIT thinking, but even that's not quite correct. Because it's not that growth is being turned "on" so much as growth is being maxed out under certain conditions, and if those conditions are met, then you've done all you can in that set to grow.

So, the hypertrophic potential of a set is only maxed out when two things happen:

1) Sufficient total time/reps/fatigue

2) Sufficient levels of recruitment occur

For #1, we appear to need to do > ~5-6 reps per set. For #2, we need to reach a condition of full recruitment, either by being heavy enough or close enough to failure.

So testing this model, doing singles or triples satisfies #2, but not #1. So we'd predict that their growth potential would not be maxed out, and as per the research, this appears to be the case, though you can make up for it by doing a shitload of sets. Similarly, if we do really light weights but aren't very close to failure, we've satisfied #1, but not #2, and again, we'd predict suboptimal growth. Interestingly, like the singles example above, we can probably make up for it as long as we do enough volume, and there is some research where they still get pretty good growth doing a bunch of sets of 10 at ~60% 1 RM, for example, which is probably something like a ~15-20 RM, never really hitting full recruitment.

Anyhoo, I just thought these thoughts were worth sharing, as Greg's comments made me reconsider the arguments we had back and forth in that other thread I made on the necessity of load progression in hypertrophy. The problem I see vs. the other thread is that we were sort of concluding that growth was something tantamount to the amount of total work being done near failure, but the problem with this would be that submaximal sets seem to consistently generate as good of growth as sets to failure as long as the two criteria above are filled.

Any thoughts would be greatly appreciated. Ron, you out there bro?

https://www.exodus-strength.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=2928&start=40

I think this whole thing is a case where models can be useful without being strictly true. I think most people would agree that you need to a) recruit all or most MUs and b) induce some meaningful amount of local fatigue (i.e. not just doing 1RMs) if you want to maximize hypertrophy. Beyond that, you're just trying to come up with a model that more-or-less matches the experimental findings we have. I think the idea of "effective reps" puts you in the right direction, but it doesn't fit all the evidence we have (in Helms' dissertation study, growth was pretty similar between two groups stopping each set different distances from failure; in a recent study by Carroll et al out of ETSU, a group stopping further from failure grew substantially more than a group reaching failure each session. Then there's that old Sampson paper where growth was similar between failure and ~2 reps shy of failure). And then there's also the issue of model fitting - are we sure the hypertrophy we're seeing in the research is the hypertrophy we "should" be seeing? Do we see more growth with failure in a lot of studies simply because the subjects have more local edema? Is there possibly more sarcoplasmic hypertrophy going on with failure training (that's never been studied)?

I personally don't think we're yet at a point where we know enough to have too much confidence in any specific predictive model being "true," but effective reps isn't necessarily a bad lense to look through.

In my previous hypertrophy thread, we discussed the concept of "effective reps" that I first saw introduced by Borge/Blade. Basically the idea that the reps that really "count" in a set seem to be the ones at the end where you are in a state of maximal recruitment, particularly in sets of ~5+. So whether it's a set of 12 or 30, you only get something like 5 "effective" reps per set. Chris Beardlsey talks about the idea at length here:

https://medium.com/@SandCResearch/h...iding-failure-and-using-advanced-90e26d57bca9

What's interesting about Greg's note above is that "effective reps" doesn't seem to be consistent with the fact that training to failure does NOT actually generate more growth per set. One of the consistent findings is that sets that are even near-ish failure, like 2+ reps away, seem to generate just as much hypertrophy, usually. If there are only 5 effective reps per set as per the Beardsley thinking of effective reps, then missing something like half of those should very much NOT result in identical hypertrophy. But it seems to all the same.

Ron and I were previously speculating that sufficient work at high levels of recruitment and rate coding are necessary to grow optimally, but I'm not sure how to reconcile the rate coding model with this data either. Meaning that not all the motor units' rate coding are maxed out in submaximal sets that are in at least the ballpark of failure (probably still full recruitment), but still they seem to generate as much hypertrophy.

I was reminded of the old idea of growth being turned "on" ala HIT thinking, but even that's not quite correct. Because it's not that growth is being turned "on" so much as growth is being maxed out under certain conditions, and if those conditions are met, then you've done all you can in that set to grow.

So, the hypertrophic potential of a set is only maxed out when two things happen:

1) Sufficient total time/reps/fatigue

2) Sufficient levels of recruitment occur

For #1, we appear to need to do > ~5-6 reps per set. For #2, we need to reach a condition of full recruitment, either by being heavy enough or close enough to failure.

So testing this model, doing singles or triples satisfies #2, but not #1. So we'd predict that their growth potential would not be maxed out, and as per the research, this appears to be the case, though you can make up for it by doing a shitload of sets. Similarly, if we do really light weights but aren't very close to failure, we've satisfied #1, but not #2, and again, we'd predict suboptimal growth. Interestingly, like the singles example above, we can probably make up for it as long as we do enough volume, and there is some research where they still get pretty good growth doing a bunch of sets of 10 at ~60% 1 RM, for example, which is probably something like a ~15-20 RM, never really hitting full recruitment.

Anyhoo, I just thought these thoughts were worth sharing, as Greg's comments made me reconsider the arguments we had back and forth in that other thread I made on the necessity of load progression in hypertrophy. The problem I see vs. the other thread is that we were sort of concluding that growth was something tantamount to the amount of total work being done near failure, but the problem with this would be that submaximal sets seem to consistently generate as good of growth as sets to failure as long as the two criteria above are filled.

Any thoughts would be greatly appreciated. Ron, you out there bro?

Last edited: